A View from the Bridge - Feb 2019

As the clock ticks down towards the Article 50 deadline of March 29th, longer-term U.K. interest rates find themselves pretty much back where they were before the Bank of England decided to lift base rates from 0.25% in November 2017. For example, 5-year swap rates were 1.09% when the bank first raised base rates to 0.5%, they are currently just 1bp higher at 1.10%, leaving the entire term premium reflecting less than a single interest rate increase.

Gridlock in parliament portends fears of a no-deal exit despite the vast majority of politicians doing their utmost to rule out any such possibility. However, not all of the blame for the softness in the UK economy falls at Brexit’s door. The global economy began to slow in the second half of last year and this has continued into the early stages of 2019, with the IMF downgrading its global growth forecast by 0.2% to 3.5% for the year. The Eurozone in particular has seen a significant softening in activity, with a few member countries now flirting with recession at both an official and indicator data level. Eurozone growth forecasts for 2019 and 2020 were revised down by 0.6% and 0.1% respectively. The U.S. is proving much more resilient against the global downdraft, but it’s worth remembering the economy is still benefiting from the tail-end of a substantial fiscal stimulus and the Fed has been able to cushion the blow to equity markets experienced in the final three months of last year by taking any premium for further tightening out of market interest rate expectations.

The bigger test for the sustainability of the US expansion arguably begins now. A partial resolution to both the Congressional impasse and the trade dispute with China has already been reflected to some extent in risk asset prices (S&P +7%). The sustainability of China’s own domestic demand growth is actually much more important than any resolution to the trade dispute, in what remains a demographically challenged developed world economy. Financial conditions tightened considerably at the end of last year and some of this has been mitigated by global central banks turning more dovish in recent months (Fed, ECB, BOE, RBA and RBI), but credit spreads generally remain well above early 2018 levels and the typical lags are expected to impact growth over the next 6-12 months.

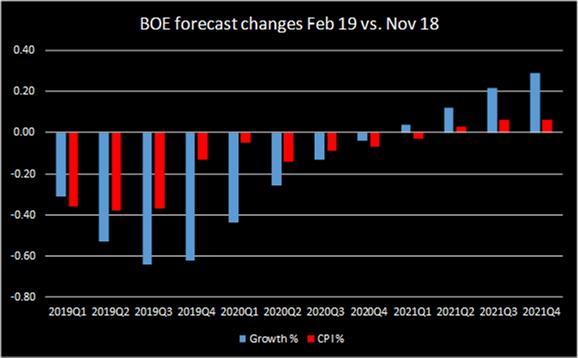

So returning to the UK outlook, the Bank of England lowered its 2019 growth forecast to 1.1%, down 0.6% from its November projection and the lowest since the aftermath of the financial crisis. However, the outlook for 2020 and 2021 were largely unchanged to slightly stronger (the BOE continues to calibrate its forecasts around an orderly exit on March 29th). Brexit uncertainty has coincided with a generalised slowdown globally (the UK and Eurozone forecasts revisions were identical) with lower oil prices further dampening the inflation outlook, meaning that the likelihood of UK rates moving up sharply even in the event of a deal being agreed has lessened. The market interest rate curve used by the Bank to calibrate its inflation forecast implied about 1 to 1.5 25bp hikes over the next 2-3 years and this left inflation only marginally above the 2% target at the forecast horizon, whereas 2-3 hikes were needed in November to deliver the same projected outcome for inflation.

In summary, the UK rates outlook is being buffeted by both Brexit uncertainty and headwinds to global growth. A no deal Brexit would obviously bring considerable uncertainties beyond the BOE’s central forecasts, but it is difficult to envisage higher policy rates in such a scenario. An eleventh hour Brexit deal should bring stark relief and a bounce in investment spending (this fell almost 4% in 2018), but the global outlook still matters for an open economy such as the UK and if it remains subdued it may continue to tie the BOE’s hands.

PegasusCapital - 20/02/2019

Whitepapers / Articles

A View from the Bridge - February 2026

PegasusCapital - 06/02/2026