A View from the Bridge - May 2022

Over the past six years the U.K. economy has been buffeted by a prolonged series of demand and supply shocks. The first of course being the decision to leave the European Union and its ongoing effect upon international trade, secondly the onset of and emergence from the sequence of COVID restrictions and most recently Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Each of the above shocks has had both distinct and common effects upon various sectors of the UK economy. The most obvious effect at present is upon consumer price inflation, with the Bank of England alerting everyone to the prospect of a double-digit increase in the cost of living later this year, bringing back memories of genuine hardship experienced in the 1970s and early 1980s for those of us old enough to remember.

Worryingly, we are seeing an even greater increase in the cost of inputs to the business sector, the ONS reported that annual business input costs had risen by 19.2% in March, the highest rate since records began. Business output prices have increased by 11.9%, highlighting a significant amount of pass through, but nonetheless the remaining 7% or so is being absorbed in margins or attempted cost reductions. The economic hardships being experienced by broad swathes of the UK working population may limit the extent to which businesses can pass on further cost increases. Basically, both the consumer and business sectors are experiencing historically significant falls in real purchasing power raising the spectre of stagflation, but not in the historical sense of wages spiralling higher given diminished unionism.

So why is the Bank of England still on a flight path to higher interest rates despite the obvious detrimental outcomes to both consumers and businesses? Nobody should envy the Monetary Policy Committee’s task in steering the UK economy through the current storm. Their 2% inflation target is so far below prevailing inflation rates that setting interest rates at an appropriate level to deliver convergence at the 2- to 3-year horizon within a standard statistical error bound is nigh on impossible. Arguably the ideal way to view the Bank’s predicament is imagining being in a tunnel where the light at the end is yet to come into view. Therefore, the Bank will continue to feel its way through the darkness with interest rate increases until it sees evidence of these supply shocks easing, genuine stress in the underlying economy (via equity and credit markets), weakness in the wage setting element of the labour market or a combination of them all.

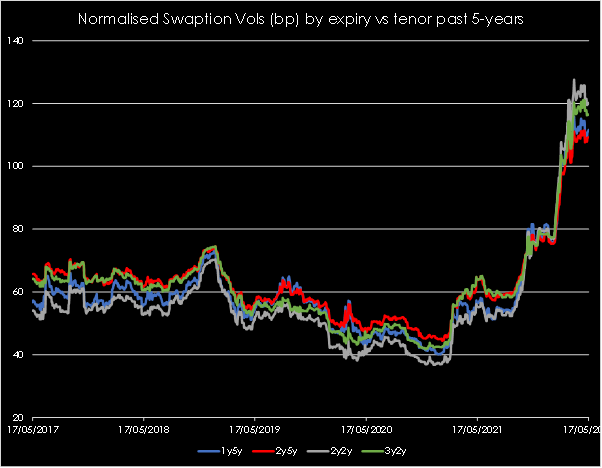

The market, via the 3-month SONIA futures curve, believes that interest rates will peak at 2.25% to 2.50% in the summer of next year. This is down a bit from a peak of 2.75%-3% shortly before the May 5th BOE policy meeting, when recession risks were raised in the policy statement. This still means that interest rates are expected to more than double from their current level of 1% after rising rapidly from the 0.1% emergency level late last year. It is easy to see why there are many claiming that with inflation running so hot that these expectations are nowhere near high enough whilst there are equally as many claiming that any tightening above current market expectations could send the economy into a sharp recession. Therefore, although the median expectation is for interest rates to peak between 2% and 3%, the true market uncertainty can be seen in the implied volatility of options on SONIA interest rates over the next few years (see chart below).

The implied volatility of SONIA swaptions has doubled versus historical norms (currently over 100bp per annum), meaning that the cost of uncertainty has increased. As an example, the expectation that interest rates reach 2.5% by June next year has a confidence interval range of up to 3.5% or as low as 1.5%. For borrowers who typically choose between caps and swaps to hedge their interest rate risk the decision around which product to choose is perhaps skewed towards locking in a fixed rate over a 2- to 3-year period at this juncture as the prevailing level of base rates and implied volatility makes the breakeven on caps quite expensive versus fixed rate as long as the banks don’t start increasing their credit charges (spread to mid swaps). However, careful analysis is still needed when looking to hedge over 5 years. This is because the SONIA interest rate curve begins to decline again from 2023 to 2027, and additionally the risk of a policy mistake emerging, demanding significant easing of policy, increases over the longer time frame, potentially benefitting a cap hedge over a fixed rate hedge despite the high initial costs.

Source: Pegasus Capital, Bloomberg Financial LP

PegasusCapital - 28/01/2021

Whitepapers / Articles

A View from the Bridge - February 2026

PegasusCapital - 06/02/2026